Or: A reflection on the sadistic humour of the goddess Clio.

By Dr Tamson Pietsch

There is an alternative origin story for the Floating Univeristy that does not (at the moment) get told in my book.

It begins like this:

Some time in the cold New York winter of February 1925, six men met for dinner on a ship moored on the East River at the southeastern tip of the Bronx. The Professor, the ship’s Captain, the diplomat, the newspaper Editor and the Quaker had been brought together by a Greek refugee called Constantine Raises.

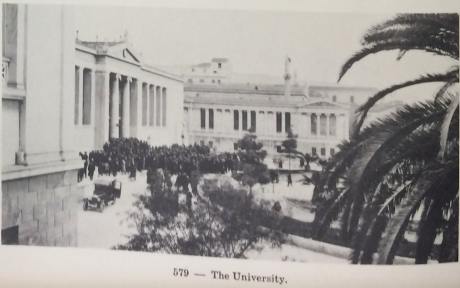

Raises had met the Professor on a hot summer’s day five years earlier. The American was travelling with a party of his students who were touring the cultural and classical sites and they had made the journey out to the suburb of Zografou to visit the Univeristy of Athens, where Raises was a student. He knew a bit about Americans, having learned English as a boy at the American School at Smyrna, and he ended up showing them around the campus.

Smyrna (also called Izmir) was a city located on the Aegean cost of Anatolia. It was home to a large Greek community and under the Ottomans it was an significant port and financial centre. Raises’ father was an an importer-exporter and took his son on trips around the Mediterranean. His father enrolled him in the American School where he had learned English and it was there that he met a diplomat, the United States Consul, George Horton.

The Professor whom Raises had met at the Univeristy of Athens in 1920 was a man named James Lough, and he taught at New York University. Impressed with Raises’ fluency in English, Lough hired him on the spot to serve as translator and guide for his party and this was a relationship that continued through to the summer of 1922 when he left Athens and returned to his home town of Smyrna and the family business.

But 1922 was a bad time to return in Smyrna. The Greek army had landed in the city in 1919, beginning the conflict now known as the Greco-Turkish War, fought in the western and northwestern parts of Anatolia in the wake of the defeat of the Ottoman Empire. After initial victories won by the Greek forces, the conflict reversed course and the Turkish army recaptured Smyrna in early September 1922. Four days later a fire broke out that destroyed the Greek and Armenian sections of the city. Tens of thousands died in the blaze. Many more were killed before and afterwards, and between 25,000 and 100,000 Greek and Armenian men were deported to Anatolia, where many died.

Raises managed to escape, very possibly with the assistance of George Horton, who reportedly spent the last hours before his own evacuation signing passes that granted American protection. Perhaps Raises was one of them. Separated from his family and living in a refugee camp, like so many others from his country, he looked for ways to immigrate to the United States.

And somehow he managed to make it. Arriving in New York in 1922, Raises contacted his old friend Professor Lough, who helped him find a clerical job on the New York World newspaper, at the time edited by the renowned reporter, Herbert Swope.

But Raises was not suited to a desk job. He longed to travel and in 1924 he took a job, first as a purser on the Dollar Line’s SS. President Garfield and then as aide to Captain Felix Riesenberg who was Commander in 1923 and 1924 of the New York Maritime Academy’s training ship, the USS Newport. Riesenberg was also a prolific author of books on maritime literature and Raises helped him with research and translation of materials (reportedly Raises is acknowledged in several of Riesenberg’s books).

On his voyages with Riesenberg, the Greek from Smyrna saw first hand the effect of shipboard education upon the young cadets and on his return to New York he contacted Professor Lough, whose own attempts to launch a Floating University had already been reported in the press. At the time Lough was trying to purchase the SS President Arthur from the United States Shipping Board, the original purpose of which was to encourage the creation of a naval reserve and a Merchant Marine, so it made sense for Raises to connect him with Riesenberg.

It was Riesenberg who in early 1925 hosted the dinner party on board the Newport, but all the men present were there because of their connection to Raises. All, that is, except Andrew J. McIntosh, a wealthy Quaker, retired shipping broker, and trustee of the New York Maritime Academy. He had an interest in internationalism and Risenberg had invited him, thinking he might be interested in the Floating University project. Perhaps Raises also thought that Horton – who had only recently returned to the United States, and who was at the time writing his book, The Blight of Asia, which would tell the story of the 1922 occupation of Smyrna, the torching of the city and killing and expulsion of its Greek and Armenian citizens – would also be interested in its internationalist and educational aspects.

McIntosh was taken by the idea of the Floating University and, much to Lough’s surprise, at the dinner he handed over a cheque for $25,000. Together they formed the University Travel Association, with McIntosh as President, Lough as director of educational affairs and Raises in charge of the itinerary. Their aim was to launch a voyage in September of that year (1925). Lough managed to obtain a charter from the New York Department of Education giving him permission to operate a university on a ship, and he convinced New York University to sponsor the project. Herbert Swope wrote a publicity-generating piece in the New York World, and the Holland America Line offered the use of one of their ships – the SS Ryndam, at the time sitting idle in Rotterdam – for a token fee. Although not enough students signed up for a sailing in 1925 as initially planned, the Floating University became a reality in 1926, when 500 students sailed on the Ryndam, accompanied by Professor Lough, Andrew J. McIntosh and Constantine Raises.

This origin account can be found in the only existing short history of the Floating Univeristy that I have come across. It was published in 1998 in a magazine called Steamboat Bill and written by Paul Liebhardt, a photographer, author and one time teacher on Semester at Sea. Liebhardt, with whom I’ve been in correspondence, says that he was told the story by Raises himself, when he interviewed and photographed him in November of 1984 in San Francisco, shortly before Raises death. A version of the story also appears in the biographical note prefacing the collection of Constantine Raises’ papers held by the University of Colorado, Bolder, archives. It reappears in several accounts across the internet.

It is a wonderful story. But I just can’t be sure that it’s true …

[Editors Note: This piece originally appeared on Cap and Gown: blogging the original knowledge economy, Tamson Pietsch’s excellent research blog, republished here with permission from the author. This article forms part of a series on the Floating University, which can be found here: https://capandgown.wordpress.com/category/floatingu/%5D]

Image Notes: The 1926-27 Floating University visit to the University of Athens. Walter C Harris, Photographs of the First University World Cruise (1927)

One reply on “Chasing Constantine Raises (Part 1)”

[…] from Part 2 and Part 1 of Chasing Constantine […]

LikeLike